#3 Geology / What's under your feet?

*This is the third post in a pop-up, limited edition newsletter about DC from unexpected angles. The first was about wildlife, the second about the founding of DC, and here’s the intro to the project.*

If you were to walk across DC, starting at bottom of the diamond to the top, you'd also feel like you're walking up — once you hit 16th St, it would feel like climbing a story every mile — until you hit the peak at Fort Reno — at which point you would have climbed about 40 stories.

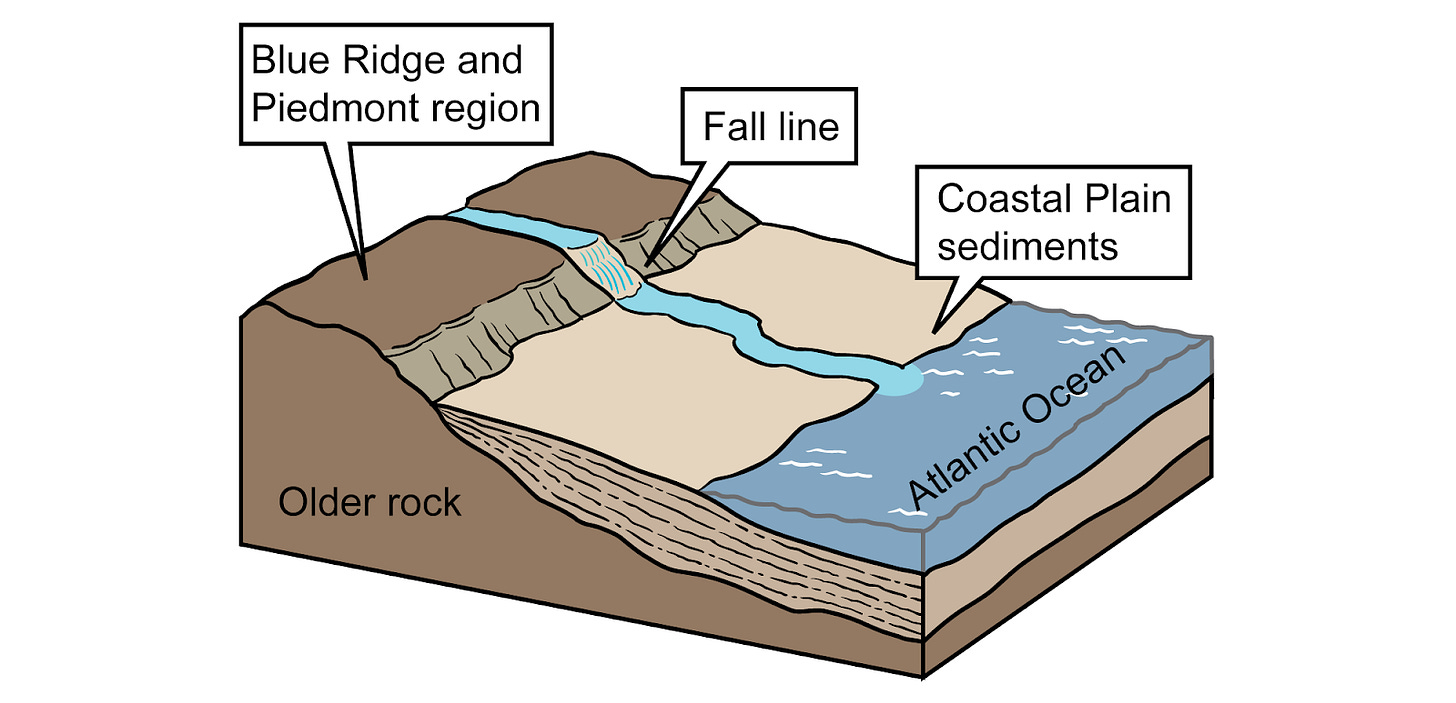

Turns out that DC is on the confluence of not only two rivers1 but two distinct geological foundations — the sedimentary Coastal Plain to the south and rocky Piedmont to the northwest.

The Coastal Plain lies quite a bit lower than the Piedmont — so much lower that it was originally under the Atlantic Ocean millions of years ago!2 So what we’re on now is the ancient seabed.

The city’s geology has shaped everything from the soil we have to how we built the Metro3 to even the fact that the DC area was chosen as the country’s capital. That’s why you gotta know where you stand — metaphorically but also literally.

The boundary between the two geological provinces is called the “Fall Line” – this was the prehistoric shoreline of the Atlantic Ocean.

DC is not the only city on the Fall Line, and it’s not an accident that we’re here. There’s a phenomenon called “fall line cities”, referring to the fact that if you draw a line through major southern East Coast cities, you effectively trace out the fall line. How come?

The transition between these two geological zones is pretty sharp: from Piedmont’s hard rocks making up rolling hills4 to suddenly falling down to the seabed of the Coastal Plain. When rivers hit this fall, they create waterfalls or rapids — which means faster-moving water, which in turn means a source of energy for powering mills.5 This also formed the “head” of navigation, or the last point that ships could traverse, going from easily navigable, wide waters that we see next to Georgetown Waterfront to the rocky rapids like those near Great Falls. All this made DC – and other cities like it — a good place to both make goods and also ship them out.

So to return to the original question — what are we standing on? We’ve covered the first part of the answer, which goes all the way down to the rocky foundation of either the Piedmont or Coastal Plain. Above that, it’s mostly soil.6 But sometimes it’s not that simple.

When I read that Washington chose the nation’s capital to be on the Potomac, I didn’t realize that it was literally true. In the original plans, the White House was almost on the banks of the Potomac, and what we know as the National Mall was just marshes and wetland that would be submerged by the Potomac’s tides twice a day .

So the ground under the National Mall was built … by draining these swamps and then dumping out the sediment accumulating in the river. Take a look at this photo from 1917 of the Lincoln Memorial surrounded by wetland plants to get a sense of the shaky foundations of our democracy (sorry).

And here’s the original DC coastline (before) and the one today (after).

We carry that legacy with us today. The Coastal Plain is low-lying, so as sea levels have risen by a foot and the fake land has settled by three, twice a day, the Potomac breaks free of the seawall7 and floods the path around the Tidal Basin.8

It also drowns the cherry trees in the dirty waters of the Potomac, hence the social media phenom Stumpy, a cherry tree that like 158 of its brethren was removed as part of an initiative to rebuild the seawall.

Raising the sea wall is ultimately only a stop gap measure — sea levels are going to continue to rise. But what was there before — the banks of the river — did that work for us by stabilizing the shoreline, so some advocate for a “living shoreline”, which would bring back wetland plants and oyster reefs to recreate that buffer with the water and protect against erosion.

It’s not just the National Mall; the ground beneath our feet is deceptive in other parts of the city too. Under what is now Kenilworth Park and the Benning Golf course is the site of Kenilworth Dump — an open landfill which would regularly be lit on fire to burn down the trash.9 Maybe it was my imagination, but I felt walking across the park that there were little uneven mounds, hinting at the uneven rubbish underneath.10

This feels like an easy metaphor, about how the ground beneath your feet is unstable, but it’s true! Sure it’s not as extreme as Santiago de Chile or Tokyo, but just like those cities, the (literal) foundation of our city has been shaped first by geological forces for millions of years and then human ones to serve our purposes. We have our history — and our future — etched into the ground beneath us.

Microadventure

Walk along the former Atlantic seabed to the shoreline all the way to the highest point in DC, at Fort Reno Park!

The Potomac and Anacostia rivers — post to come on this!

To be precise, between 5 and 50 million years ago; in any case, it was still under water after the dinosaurs had already gone extinct.

Basically digging really, really deep — which is why we have the longest escalator in the Northern Hemisphere! More to come.

Formerly mountain ranges (possibly the size of the Himalayas) that have been eroded — so when you’re hiking around there, you are summitting (formerly high) peaks! They were created by the collision of Africa and North America over 200 million years ago.

This was done by constructing thousands of little dams along rivers, through which you could then control the flow of water to turn a waterwheel and grind flour or make iron.

In general, the Chesapeake Bay region offered much to its settlers. You could traverse the area easily through all the rivers before there were roads, and there was plenty to quarry — sand, silt, clay, ironstone — used to make products like bricks or iron ore that financed the growth of the colonies. Baltimore, for example, became a center of brick and iron ore making, even exporting them to Europe (The Chesapeake Watershed).

(river)wall

Called the Tidal Basin, by the way, because it is the tidal flats, intertidal zones which are exposed in low tide and submerged in high tide.

And where a young boy, Kelvin Tyrone Mock, who had been playing tragically died in 1968

Capping landfills and building parks over them is pretty common, with examples in New York and Toronto.